Around 100 years ago, Philips developed a groundbreaking innovation of great significance to the medical world: the Metalix X-ray tube. The innovative Metalix gave Philips a leading position in the medical world.

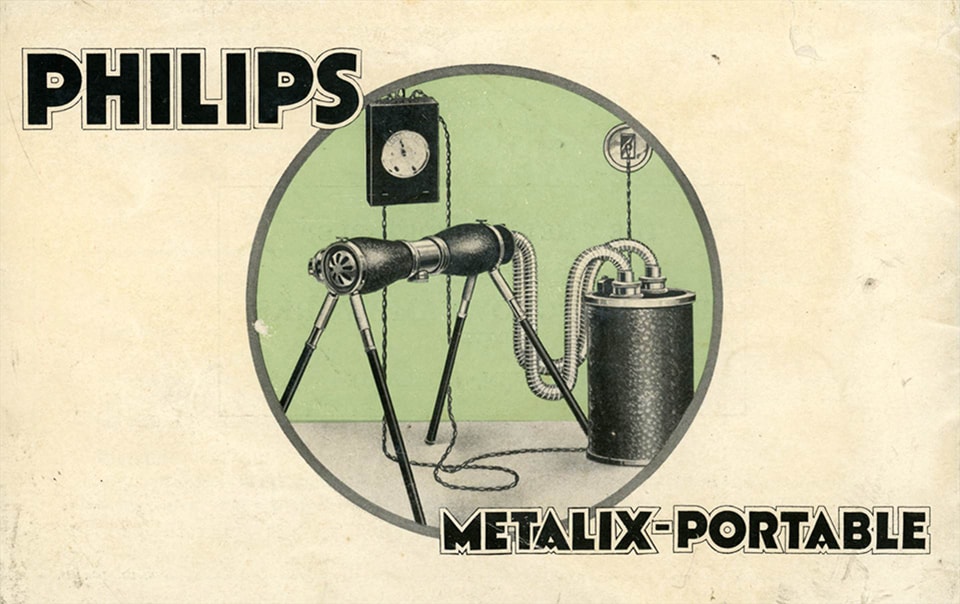

The Metalix X-ray tube was much safer than other X-ray tubes. A metal jacket stopped the unwanted and dangerous scattering of X-rays and only let radiation through, through a small opening at the bottom. A later version also had protection against high voltage, allowing doctors to use the mobile version even in patients' homes.

First patent

Before the arrival of the Metalix, Philips was already producing its own X-ray tubes. That activity originated from development work at the Philips Research Laboratory, the ‘NatLab’. This started with the repair of defective X-ray tubes at the request of Dutch radiologists, but from 1918 Philips manufactured them itself on a small scale, and a year later the company obtained the first patent in this field.

Radiation

As was common at the time, they were spherical glass tubes with no protection against radiation. Overexposure could have serious consequences for both medical staff and patients. The tube could be shielded, but that made handling the equipment cumbersome. Moreover, the tube operated at high voltage, which also posed dangers.

Metal cloak

A scientist at the NatLab, Albert Bouwers, changed this. Between 1922 and 1924, he developed a new type of X-ray tube that offered protection against both radiation and high voltage. In doing so, Bouwers made use of a 1922 invention by NatLab director Gilles Holst for joining glass and a ferrochrome alloy. According to tradition, Holst came up with the idea after a visit to the glass factory, where glass blowers dipped metal blowpipes into the red-hot glass and then manufactured the glass balloons for light bulbs.

Most advanced product in the industry

The technique discovered by Holst enabled Bouwers to design a glass cylinder and fuse fuse a ferrochrome ring in the middle to it airtight. This allowed the tube to be more compact than earlier models and shield the discharge chamber by lead. X-rays could escape only where they were needed: a small window at the bottom. A cylinder made of plastic enveloped the parts, thus securing the passage of high voltage. This made the Metalix tube the most technically advanced product in the industry and made Philips a formidable competitor in medical equipment.

Rotalix

The knowledge gained in the development and manufacture of the Metalix also formed the basis for later developments, such as the mobile Metalix Junior that doctors could use on patients at home, the Oralix for dental use and the Rotalix that provided better imaging of organs, also a Bouwers invention.

RSNA awards gold Compton medal

In December 1923, the new X-ray tube was first demonstrated at a meeting of the British Institute of Radiology in London and very enthusiastically received. However, the first version had teething problems, so Bouwers and his team had to modify the tube. The new version became a resounding success.

In 1928, a visitor to the International Radiological Congress in Stockholm noted that almost all participants had a Metalix in their stands. There was also great enthusiasm in the US. In the same year, the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) awarded Albert Bouwers the gold Compton medal for his outstanding achievements. It is also worth mentioning that Philips' first establishment in the United States (1933) was the “Philips Metalix Corporation” in Mount Vernon, New York.

Investment

Despite the success of the Metalix, the X-ray business was not yet a profitable business in the early years due to the high investment in development and manufacturing. Also, marketing lacked experience in selling the X-ray tubes. That the company continued with this nonetheless was largely due to Anton Philips' enthusiasm. In the 1920s, he said ‘we must now press on and throw some money at it.’ The new business in X-ray strengthened the company's prestige and position as a leading technology company.

Tuberculosis

Moreover, Anton Philips attached great importance to promoting public health and combating the dreaded lung disease tuberculosis in the 1930s and 1940s. Philips' Medical Service and the Metalix X-ray tubes used played a vital role in this.

Employees and their family members and later all residents of Eindhoven were screened for TB. They stood behind a screen on which the doctor could quickly see whether the lungs were affected. Only when suspicious spots were detected at an early stage was healing possible. The results were not disappointing: there were as many as two-thirds fewer fatal TB victims in Eindhoven than in other Dutch cities. A great example of social entrepreneurship and ‘improving people's lives with meaningful innovations’!

Text written by Sergio Derks

Copyright: Koninklijke Philips N.V. / Philips Company Archives.

Literature: I.J. Blanken, Geschiedenis van Philips Electronics N.V., part III, Leiden 1992; Jan Hofman, The art of medical imaging, Eindhoven 2010