“We should never forget that all technical developments do not exist in the first place to fight discomfort but to contribute to human well-being in the positive sense.”

Louis Kalff (1897-1976) grows up in an artistic environment and becomes acquainted with leading artists at a young age. He enjoys drawing and develops his talent. Kalff attends a school for applied arts for a year and then enrolls in the study of architecture at the Technical University in Delft. After graduating in 1923, he starts working at an architecture firm. However, he continues to design numerous posters and establishes his name as a graphic designer.

Louis Kalff at Evoluon (1966)

The beginning at Philips

Louis Kalff applies for a job by sending a daring letter to Anton Philips, as he recalls. "The advertising created by Philips does not reflect the significance and status of the company," he writes, referring to the use of Dutch folklore in the company’s advertisements. This bold statement earns him an invitation. Anton Philips recognizes the power of advertising and is personally involved in it. The advertisements featuring Dutch traditional costumes are very popular, but around 1916, Philips starts incorporating more modern design. On a freelance basis, advertising assignments are given to several well-known artists such as Albert Hahn, Theo van Nieuwenhuis, Leo Gestel, and others. Impressed by his self-assurance and creativity, Anton Philips appoints the inexperienced but talented Louis Kalff as the Artistic Director of the Advertising Department. At that time, the Advertising Department consists of Commercial Propaganda and Artistic Propaganda. On January 5, 1925, Louis Kalff begins his career at Philips.

Modernizing the Brand

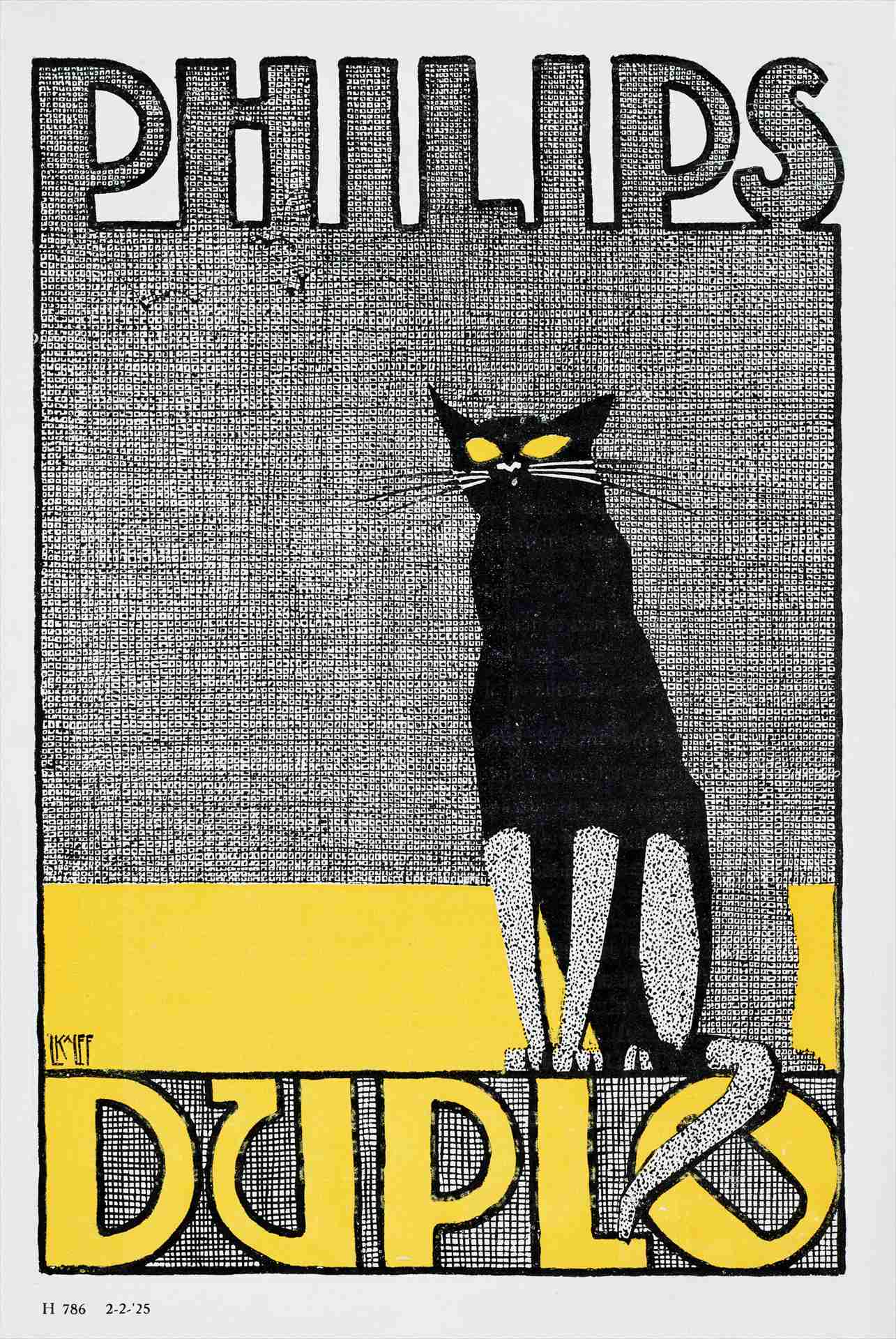

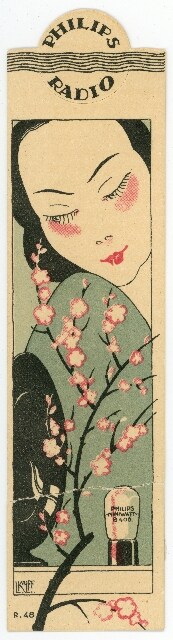

In a small attic studio at Willemstraat in Eindhoven, Kalff set up his design studio and begins his first task at Philips: giving company’s image a clear and modern look. However, his first advertisements meet with criticism. Some may consider them art, yet definitely not as advertising art, declares the trade magazine Reclame in April 1925. The magazine also finds their readability lacking. Coincidence or not, a few months later, Kalff introduces the wordmark PHILIPS in bold, distinctive block letters. At the time of his appointment in 1925, the Philips brand name is written and printed in more than twenty-five different ways. This is because each artist commissioned by Philips designed the word mark in their own style. Kalff’s strong capital letters, decorated with a few lines running through them, are the precursor to the standardized and protected Philips logo as it appears today. Additionally, he aims for standardization of Philips colors: "I was then very influenced by the primary colors: red, yellow, blue, and black," he explains as his choice. In his graphic work, Louis Kalff is often inspired by Japanese art and culture. The square block that he uses to sign his work also points in that direction.

Kalff’s first design at Philips is for Duplo car lamps (1925)

Bookmark with Philips Radio and Miniwatt radio tube advertising (1926)

Kalff attracts many talented artists and designers. He takes charge of arranging Philips stands at trade fairs and exhibitions where Philips showcases its products to the public. Here, he can also express his skills as an architect, quickly gaining a good reputation and securing large assignments for world exhibitions and other major events.

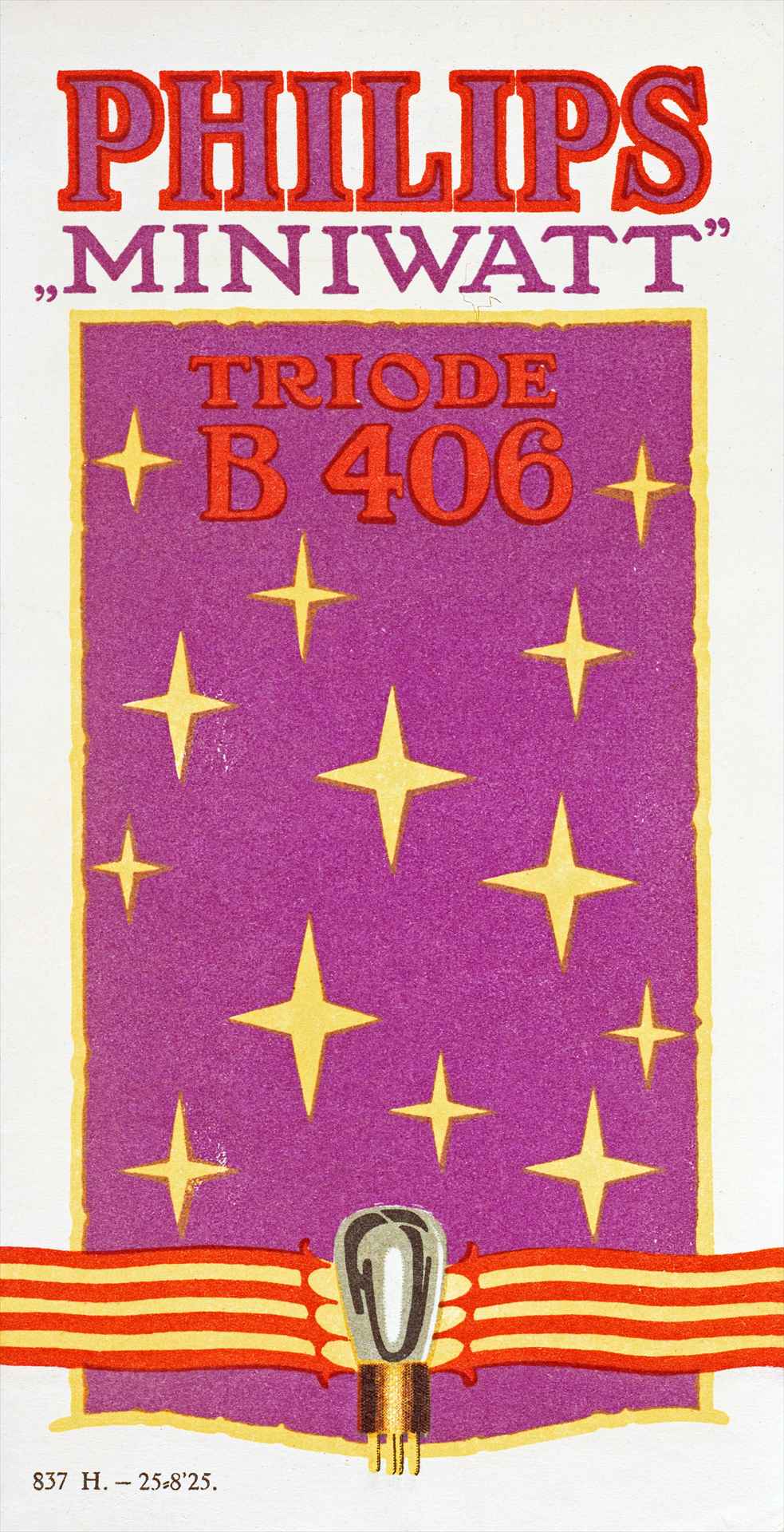

The foundation of a Philips housestyle

Between 1925 and 1929, Kalff successfully creates a recognizable Philips visual identity in a relatively short timeframe by ensuring consistency between product design, advertising material, and the design of window displays and exhibitions. During this period, the Philips circle emblem also emerges. Kalff describes the creation process as "a fortuitous convergence of elements," and continues: “initially intended merely as decoration for radio tube packaging.” In addition to posters Kalff designs packaging, starting with the 1925 Miniwatt triode B406, adorned with waves and stars symbolizing the air through which sound travels. Subsequently, these stars and waves appear as decorative motifs on radios and speakers. In 1938, Kalff combines the circle emblem and the word mark within a single shield, thus standardizing the Philips trademark.

Philips shield logo (1938)

Front cover of brochure for Miniwatt radio tubes (1925)

Radio type 930A/932A, nicknamed "Chapel radio" (1931)

The art of displaying

In 1925, Anton Philips decides to expand the product range to include speakers and radios, among other items. Kalff's advertising department is tasked with providing the "aesthetic support" of the new products. Kalff refers to this as "the art of display." Nowadays, we call it product design. Industrial design is not yet a familiar concept at the time, but Kalff is among the first to understand that a product's design is as crucial as its function: the consumer's eye also seeks satisfaction. In his view, good industrial design is essential for commercial success. Kalff designs the first Philips radios from the 1920s and early 1930s and also the first loudspeaker, the dish-shaped speaker from 1926.

Loudspeaker designed by Louis Kalff (ca 1926-1929)

The first Philishave, type 7730 (1939)

Around 1930, this activity is organized into a separate department known as ARTO (Artistic Product Design). For decades, Kalff, as General Art Director, assesses products according to functionality, aesthetics, and their recognizability as a Philips product. Each new product has to be "kalffed" before it can be put on the market. Technique and aesthetics merge into a style that defines the Philips brand.

Architectural lighting design

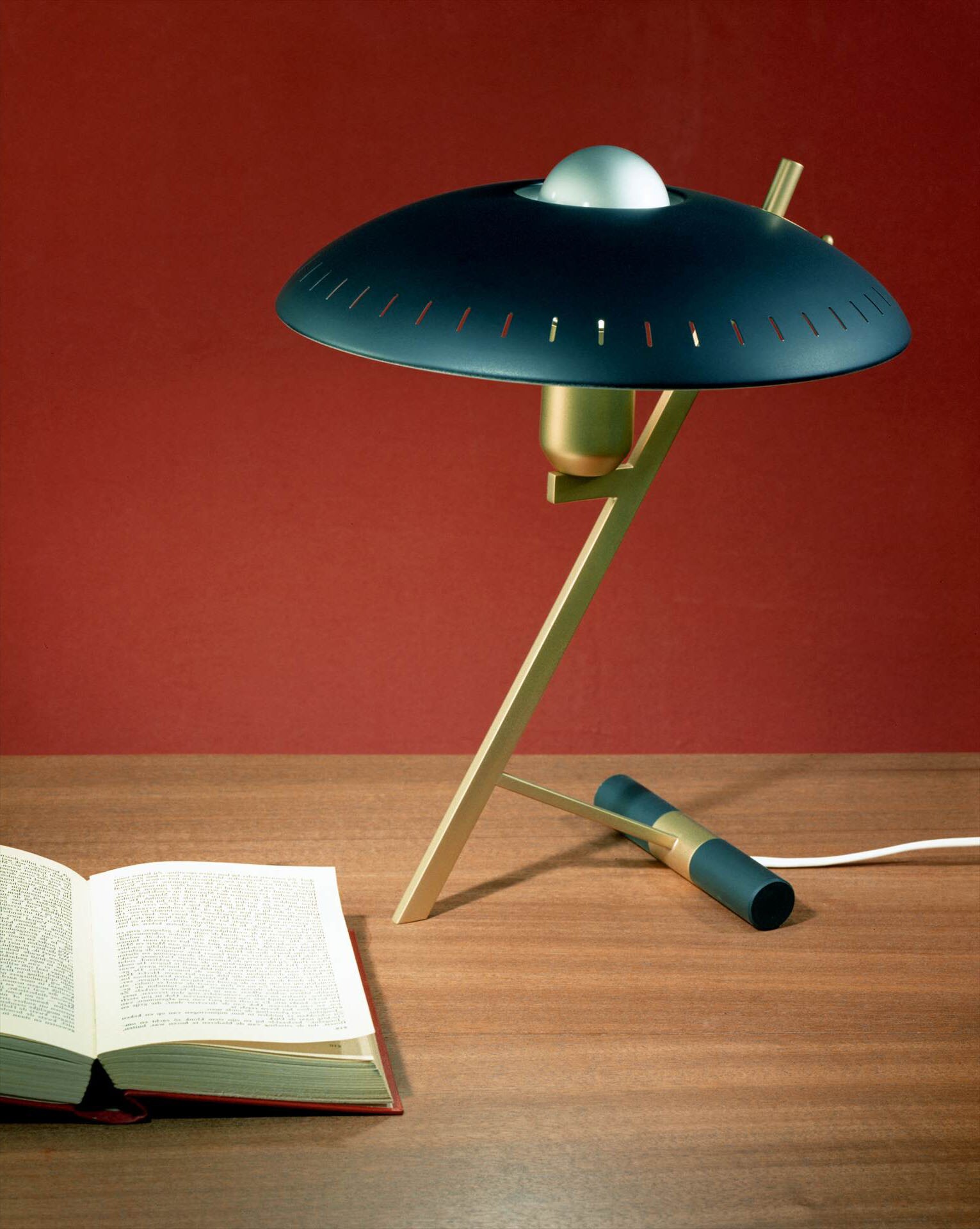

Louis Kalff has a great passion for architectural lighting design: "Bright ideas emerge in a well-lit environment." Starting in 1925, Kalff is responsible for the trade fair stands and showrooms, and orchestrates the spectacular light shows at world exhibitions in Antwerp, Barcelona, Paris, and Brussels. He introduces indirect lighting and establishes the Lighting Advisory Office in 1929. He lectures on his vision of lighting as an integral part of the overall design, encompassing both the exterior and interior of a building. Leading architects such as Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Gio Ponti seek his advice. Human beings are central to Louis Kalff’s architectural lighting design. "How does lighting contribute to human happiness?" he asks himself and demonstrates how powerful lighting can make dark streets safer, transform terraces into vibrant seas of light, and fill living rooms with warmth and coziness. In the second half of the 1950s, Philips launches a new range of luminaires designed under Kalff's supervision, inspired by space and space travel, the so-called “space age design movement”. Household lighting becomes not just functional but also mood-enhancing. Some of his iconic, timeless lamps remain celebrated design masterpieces to this day.

The Z-lamp inspired by Kalff (1958)

The illustrator shaping tomorrow

Kalff expresses his faith in the future not only through the design of lamps but also by helping to lay the foundations for professional associations and educational courses in industrial design, including the later Design Academy Eindhoven.

Kalff (left) in conversation with Le Corbusier and Edgard Varèse (composer of Poème Électronique) at the Philips Pavilion Expo Brussels (1958) He initiates the creation of the futuristic pavilion for the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958. Kalff envisions showcasing not just the latest company innovations but demonstrating the possibilities of technology through an architectural masterpiece combining image and sound. For this he asks the world-famous French architect Le Corbusier. The Philips Pavilion, where the Poème Électronique was experienced, is still considered essential study material for architecture students. Two years later, in 1960, Kalff retires but remains connected to Philips as an advisor. In 1966, he creates his most renowned work, the Evoluon, the iconic futuristic building in Eindhoven, which he designs together with Leo de Bever. In this way, he influences the company's aesthetic for over forty years, leaving a lasting impact. Text: Miriam Lengová, Philips Company Archives

Source: Philips Company Archives

Copyright: Koninklijke Philips N.V.

New exhibition at the Philips Museum: Impact through Design

Design is much more than colour, shape and material; it is about creating a better experience for the people who use the product.

From 21 June, the new “Impact through Design” exhibition at the Philips Museum celebrates 100 years of Philips Design. This fascinating exhibition will take you through iconic designs by Philips, from past classics to future innovations.