The Evoluon. A good idea has many fathers.

"Everyday life just cries out for a spark of individuality, originality. [...] The people entering this building can discover things, look around with children's eyes." (Louis Kalff, Eindhovens Dagblad 23 September 1966)

The Evoluon, designed by architects Louis Kalff (head of Philips Design from 1925 to 1960) and Leo de Bever, was built to mark Philips' 75th anniversary and festively opened its doors on 24 September 1966. Two years later on 21 November 1968, the Evoluon welcomed its millionth visitor.

Project '66

The Evoluon was not Philips' first exhibition space in Eindhoven. Before the Second World War, the company already had a history museum in the company school, which housed a permanent exhibition. This museum was destroyed by a bombing raid on 6 December 1942. In the Demonstration Laboratory (1951), today's Philips Museum, light applications were shown, in the ELA studio (1948) product demonstrations were given with radio and television sets, film equipment, etc. Both demonstration locations were popular with professionals as well as amateurs and day-trippers. After the first postwar world exhibition in 1958 in Brussels, where Philips made a very positive impression with the Philips pavilion, the Board of Management came of the opinion that it would no longer participate in the world exhibitions and would rather set aside the sums of money for the establishment of a permanent Philips demonstration center and (historical) museum, along the lines of a small expo. One did not just think about the presentation of products and the company’s history, but also: What do you do with (foreign) guests in Eindhoven?

How do you motivate staff for the company?

On 2 January 1961, the Board of Directors agreed to Frits Philips' proposal that instead of participating in the world exhibitions, "we should establish a building in which, in the first place, a museum could be set up, along with an ever-renewing exhibition of Philips products". The building could serve a dual purpose: "In the first place, it would be a spectacular remembrance of the 75th anniversary, while in addition we [Philips] would have the possibility of accommodating the many visitors in this building (which could house a cinema and a restaurant), who cannot be received in the factories at the moment, or, if they are, cause a disruption to the work there." This was the beginning of Project '66.

The inspiration

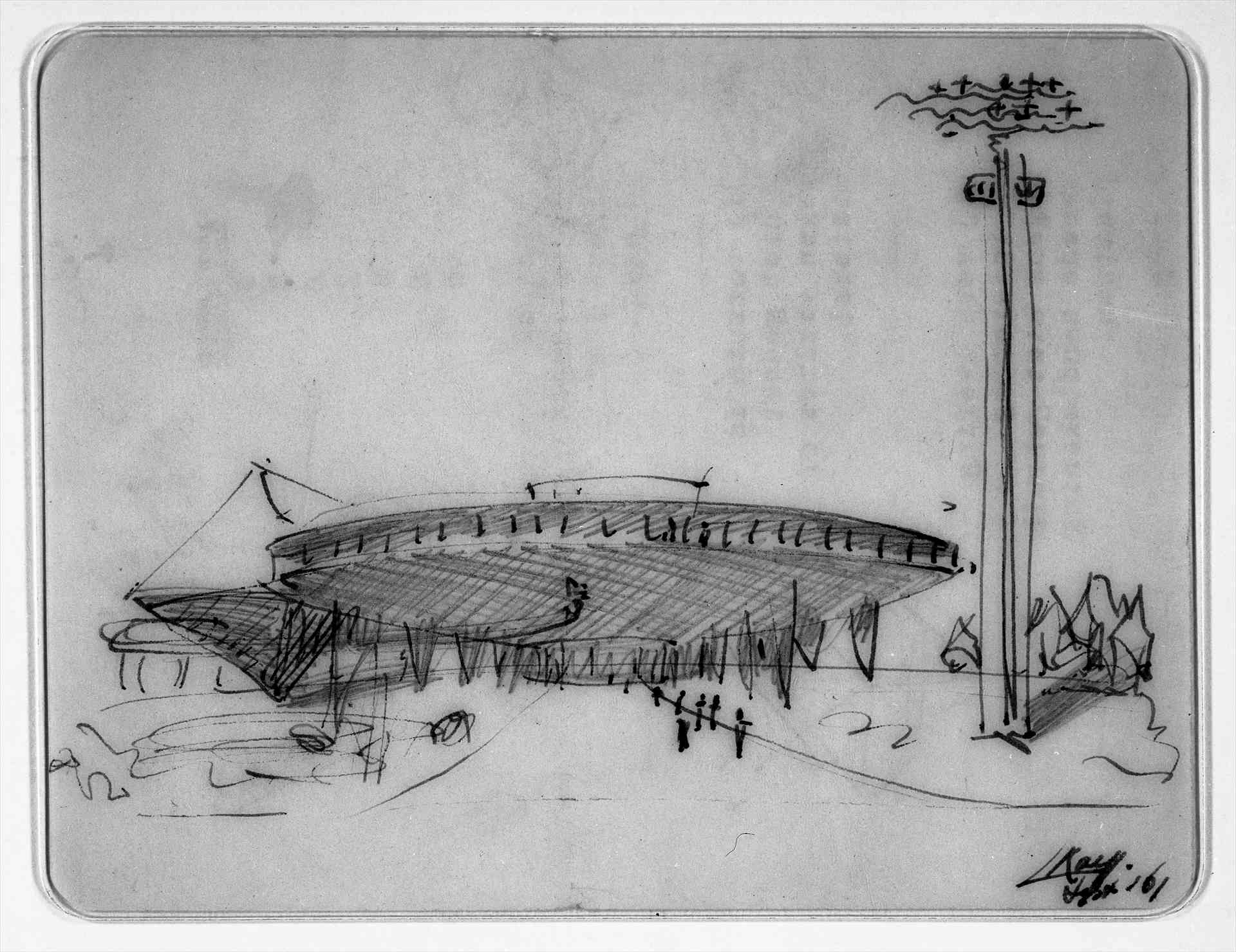

The first sketches of the building were also by Louis Kalff. As Frits Philips described it in his autobiography 45 years with Philips over lunch, sketched on the back of the menu, when he asked about Kalff's vision. The building resembling a spaceship was believed to be the most appealing. "I thought about future, weightlessness, science fiction," Louis Kalff said about the design process of the new demonstration building, "The building had to be projected into the future and trigger the imagination." The futuristic saucer shape was obviously meant to express Philips' advanced technological competence.

Louis Kalff, approached by Frits Philips, then came up with a proposal to merge the functions of the Philips museum, the Demonstration Laboratory and the ELA studio into a single reception center, which, in addition to the history of the company and the exhibition of Philips products, would also contain "presentations of the technical and physical foundations on which the operation of our [Philips] products rests." As inspiration, he referred to the Palais de la Découverte in Paris.

Kalff found another possible inspiration in architect Ralph Tubbs' impressive Dome of Discovery building with its associated element Skylon of Vertical Feature. This "temple of science" was one of the main attractions of the Festival of Britain in London organised in 1951. Louis Kalff was asked by the organisers of this festival to provide advise on the lighting. Additionally, Kalff offered advice on lighting for the Pleasure Gardens in Battersea Park, which was designed by James Gardner. James Gardner would come to leave his signature on Project '66 fourteen years later.

Future-oriented

This optimistic connotation in the name Evoluon inspired Prof Dr Jan F. Schouten, scientific advisor to the Physical Laboratory and director of the Institute for Perception Research, to come up with the philosophy behind the exhibition, which, above all, should not To visualise the exhibition ideas and presentations, the expertise of renowned English exhibition designer James Gardner was called upon.

From 1961, all sorts of ideas were proposed about what Philips could present in this building. Industrial, scientific and technological progress as well as its impact on society against the backdrop of Philips products was the guiding principle for the exhibition to be set up in the futuristic building. This vision was reflected in the name Evoluon, which was given to both the exhibition and the building. In March 1961, Louis Kalff suggested that an exhibition expert with extensive experience in the field be attached to the project, who "could conceive a unity out of a diversity of possibilities and desires". This expert was Jacques Kleiboer, the creator of the name Evoluon "an essentially optimistic concept, offering hope for the future", according to Kleiboer.

have a static character, should not be a showroom for Philips products, should not linger in the past, but rather should dare to look ahead. Furthermore, 120 specialists from the company were brought together to shape the exhibition in 18 working groups based on Schouten's philosophy.

See, discover, experience

At the Evoluon, visitors were not just spectators, but were also challenged to be an active part of the exhibition. This interaction appealed not only to professionals and technicians, but also to layman, both adults and children. The 'school trip Evoluon' was an experience to remember for a whole generation of schoolchildren. Even among those who had a little less affinity with technology. "I find that exhibition fascinating, even though I don't understand everything," in the words of one visitor. Jan Schouten and James Gardner's interactive exhibition concept was new to the Netherlands and was emulated in technology-focused presentations such as the NEMO in Amsterdam. To the disappointment of many, the Evoluon closed its doors in 1989. It was no longer justifiable for Philips to bear the high operating costs. However, the iconic flying saucer remained an important symbol of the technological strength of the Eindhoven region. Over the years, there have been numerous initiatives to give the Evoluon a public function again. Supported by a number of cultural funds, Next Nature Network eventually succeeded in making that ambition concrete. In line with Jan Schouten's intention, they want to take visitors into the evolutionary relationship between humans and technology. The opening exhibition RetroFuture (24 September 2022) focuses on imagining the future in the past and present. "The Evoluon was built in the 1960s as a hopeful future-oriented place where everyone could review and discuss new technology. With RetroFuture, Next Nature once again gives that significance to the extraordinary building." (Koert van Mensvoort, founder and creative director of Next Nature, 2022).

Jan Schouten saw something in a future-oriented exhibition, but he thought the preliminary plans were too technically oriented: "There are already enough technology oriented museums." He submitted an alternative plan, proposing that instead of technology, the focus should be on the dynamics of the relationship between humans and technology and the role Philips as a company and its products in it. "This evolutionary trademark is missing from most exhibitions," Schouten wrote in his argument. Focused on the world of tomorrow's generation, the exhibition should give an impression of how science and technology will evolve in the future. The dynamic, evolutionary, future-oriented nature would make the exhibition a unique event, Schouten said. The educational element was emphasised. The alternative plan was accepted by the Board of Governors.

Text by Miriam Lengová, Philips Company Archives.

Copyright: Royal Philips / Philips Company Archives.