The Philips Museum has been hosting the "Gerard Philips" exhibit since April 5, 2023. One of the eye-catchers from this modest exhibition is Gerard Philips' handwritten notebook. The notebook was written in the first three months of 1893; a unique insight into the thoughts and actions of Philips' founder. This is an account of the research into the contents of this notebook by Gerard Philips and is published on the day he was born exactly 165 years ago.

Portrait of Gerard Philips (1858 - 1942).

March - May 2023, Philips Museum, Eindhoven

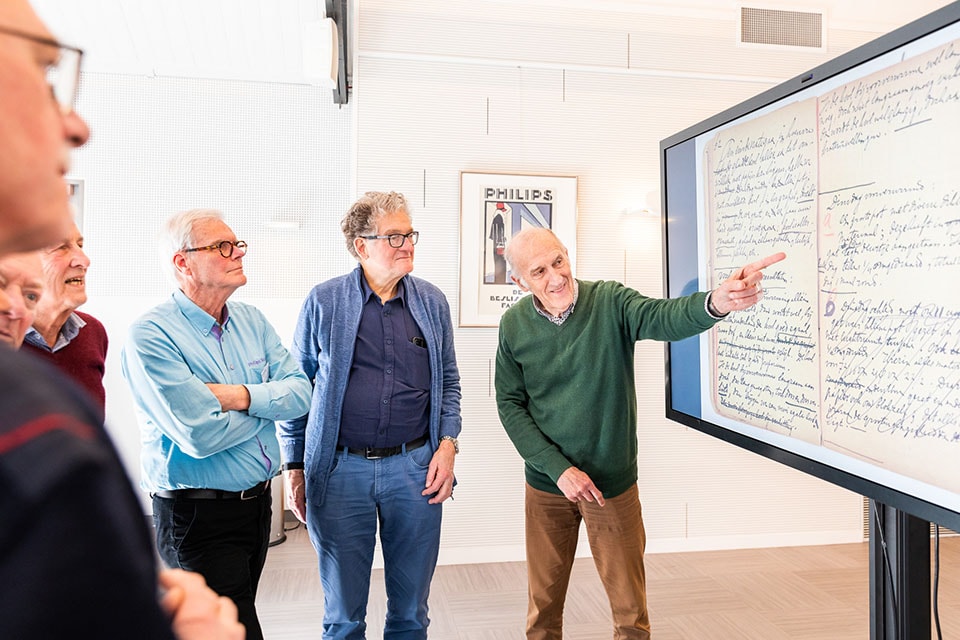

Present on March 14, 2023 are seven volunteers and experts from the Philips Museum who have earned their spurs within Philips in various disciplines of chemistry, electrical engineering and history: Bert, Jan, George, Henk, Herbert, Jan (number 2) and Sergio. Marien and Cas of Philips Historical Products read along in the background.

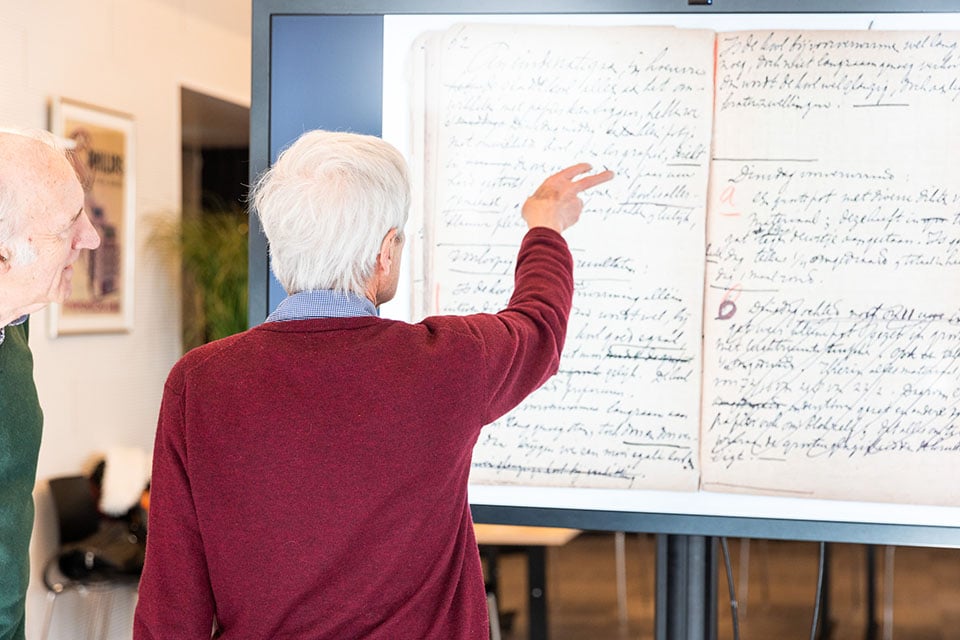

Philips Company Archives has completely digitized the notebook. The first question is whether the handwriting is legible. 'Oh,' says Jan, 'this is exactly our handwriting, this is how we boys learned it all.' That's encouraging.

Sergio explains something about the background of the notebook. 'It begins on Tuesday, January 31, 1893, and ends Monday, March 6, 1893, exactly 130 years ago. Coincidentally, the days also synchronize with the days of 2023. There must have been many more such notebooks, but because of, among other things, the Sinterklaas bombing in Eindhoven, in which many documents from the early days of Philips were destroyed, no more than one has survived.

Philips Museum experts discuss findings from Gerard Philips' notebook.

What happened before

Gerard Philips founded the company with his father as early as May 15, 1891. After preparatory work such as the purchase of machines and tools, production in the small factory on the Emmasingel gets underway in 1892. During this period, Philips & Co. made lamps for the ships of the Red Star Line and for the municipality of Amsterdam, among other things. Shipping companies were major customers. They were also one of the first customers because fire safety on board was very much improved by replacing oil lamps and gas lamps with electric light. About 11,000 lamps were made in the year 1892, but there are still many failures. Therefore, Gerard continues to improve the process.

The notes in this booklet Gerard wrote in 1893. What is the theme of the notes? What is Gerard's focus in the early months of 1893? The men doing the research want to know. Jan starts retyping the written text, expecting that if he follows it step by step, he will be able to follow the logic of the experiments better. Bert jokingly suggests setting up a laboratory at home to try out for himself all that Gerard describes.

On March 28, 2023, the experts will meet again. 'It's typically personal notes, cryptic,' says Jan. 'It's quite sloppy, written quickly as mnemonics. He doesn't finish sentences. That does make retyping difficult. You have to type it over word for word. He's not consistent in his spelling.' It is the work of five weeks. And what does this notebook tell us readers of 2023 now?

Herbert wonders what we want with it? 'If you want to know the results of Gerard's experiments, you'd better read it back to front,' he suggests. 'What strikes me is that at Herengracht he was actually already making a good light bulb but scaling it up to mass production was difficult.' Sergio explains the purpose of reading the notebook minutely: 'The importance here is that we get an impression of the difficulties and the know-how involved in being able to make a lamp in large numbers of high quality at that time.'

Herbert (left) and Jan (right)

Quest for the right filament

The theme on Gerard's mind these weeks, they conclude together, is making and perfecting industrial-scale carbon wires. In the weeks described in his notebook, you can see that he is searching for a good cellulose thread.

The quality proved very dependent on the quality of the cotton wool he used, the speed of spraying the liquid thread, the pressure you put on it, the thickness of the solution and the viscosity. Once he had a good cellulose thread, it had to be carbonized to conduct electricity. Many experiments in the booklet involve the search for the optimal charring of the cellulose wire. After all, only an evenly carbonized wire was suitable for use in a lamp.

What did Gerard come across?

Perfect carbon wires he sought. He tried to rule out everything to reach conclusions. Thus he wrote: "The obtaining of smooth or non-smooth beautiful carbon is not due to turbid Chlzn solution, not due to salt particles in Cell.solution, not due to more or less high pressure during spraying, not due to aftertreatment in water or alcohol, not due to more or less drying, not due to more or less strong tackling of the graphite, not due to the quality of the graphite, not due to the somewhat overlapping of the material during winding, but due to: [crossed out, illegible]'. If then later it appeared that he did not have the correct conclusion, he crossed out these sentences again!

The threads liquefied from cotton wool had to go into the oven. The difficult part was that Gerard was dealing with an uncontrollable thermal process, that is, a hand-fired oven. He had to set the temperature by eye. Proper charring requires constant temperature. In addition, there should be no air left in the graphite, and it had to be well pounded.

The wires also often stuck together during the charring process, as they were twisted by a number on a bobbin. And when they came out of the furnace, the wires had to be evened out.

Preparation with gas is the process of leveling the filaments - which always contain craters. The thinnest pieces of the carbon filaments glow first, and those are also the hottest. In a gas atmosphere, the wire gets sooty, and this settles first at the hottest spots; thus, an even wire is created. This production process has many steps and dependencies. So, Gerard needed many experiments to figure out what worked and what didn't.

Insights from Gerard

During the five weeks in 1893, Gerard finds out that he can only make good reproducible carbon wires if the wires first have a good preheat period. Using so-called "cokes," he first tried a low temperature, but he could not control the temperature properly. To solve that problem, Gerard ordered a gas oven. With this, he could control the temperature much better; by preheating it at 300 degrees Celsius, the charring turns out well. Furthermore, Gerard discovered a good adhesive to stick the wires to the mold.

from left to right: George, Bert, Herbert and Jan.

Gerard the developer

Bert notes that you can also get character traits of Gerard from this work. He is not a typical researcher, more of an engineer, a developer. Jan continues: "He works empirically. He does an experiment, and it doesn't come out quite what he thought it would. Then he thinks: why is that? And then he starts developing new experiments again.'

'You don't see any graphs or anything,' Bert adds and jokes: 'He obviously didn't work at the Natlab. That's probably why he hired Gilles Holst. Jan and Henk specify: 'It's typical trial and error work. A developer works toward a concrete result. The researcher is concerned with chemical and physical phenomena. A researcher wants to understand things and a developer wants to make things. A researcher comes up with a theory he wants to verify, and a developer produces a product.

Jan adds, "this was top technology at this time. How am I going to measure if I'm making steps forward?' That was a problem for him. This was a niche process.' Bert wonders if he felt alone. Gerard's quote 'in the beginning I had to do everything by myself,' does indicate that. Jan: "I think he liked the fact that he was doing it alone. And so they philosophize on.

Jan shares his findings during the survey.

What is it like to read these notes from Gerard?

Jan finds it quite exciting. 'Because the way of working appeals to me. I've been in development; first I did research at NatLab, that's where I got my PhD. At the NatLab, I also did everything myself. I can still write down the experiments I did 30-40 years ago.'

from left: Bert, George and Henk discuss the notes.

Jan resumes, "I can empathize with Gerard's issues. You see him getting closer and closer to the outcome. That whole process of setting up a trial, I recognize that very well. You don't let that go, he must have been lying awake at night too. And that you are so curious about what comes out of it. That is wonderfully exciting work. He was a good developer, you know!

For a very long time, researchers at Philips Research used notebooks to keep as evidence. At Research there were two types of books: The small ones that you put in your inside pocket and the big ones, observation books (black linen covers) with numbered pages. That official book tradition probably started with the arrival of Gilles Holst, but Gerard too was already using a small book that fit in his inside pocket.

All researchers and experts involved in the research and reporting. From left to right: Bert, Henk, George, Jan, Olga, Sergio, Herbert and Jan.

Learn more about Gerard Philips

Learn more about the Gerard Philips temporary exhibition.

Curious about who Gerard Philips was, what he did and his significance to the region? Read the article about Gerard Philips as founder, innovator, and inspiration.

Reporting on this research was written by Olga Coolen, director of Philips Museum.