Eyecatchers: the heyday of graphic design in Philips advertising

Whether it appears on packaging or brochures, bookmarks or posters, advertising plays an essential role in the marketing of new products. Between 1910 and 1965 Philips recruited many leading graphic designers and artists to design its advertising material. The posters and brochures give a beautiful picture of the times and are of a high artistic level. Moreover, the influence of art movements such as Art Nouveau, Art Deco, Plakatstil, Mid-Century Modern and even Pop Art is recognizable.

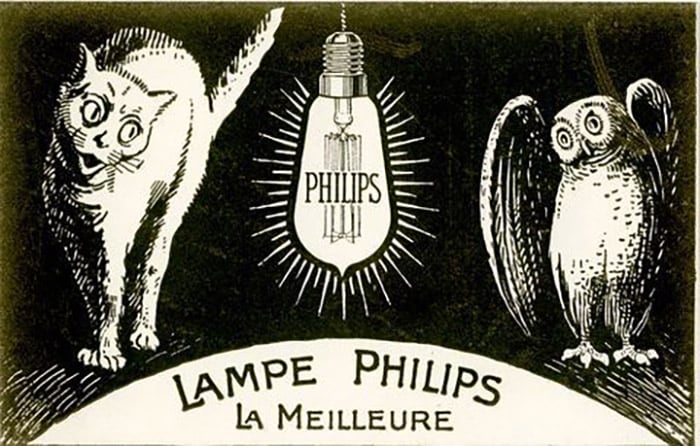

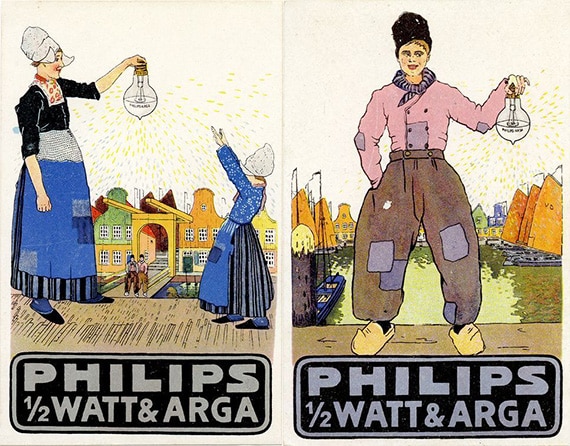

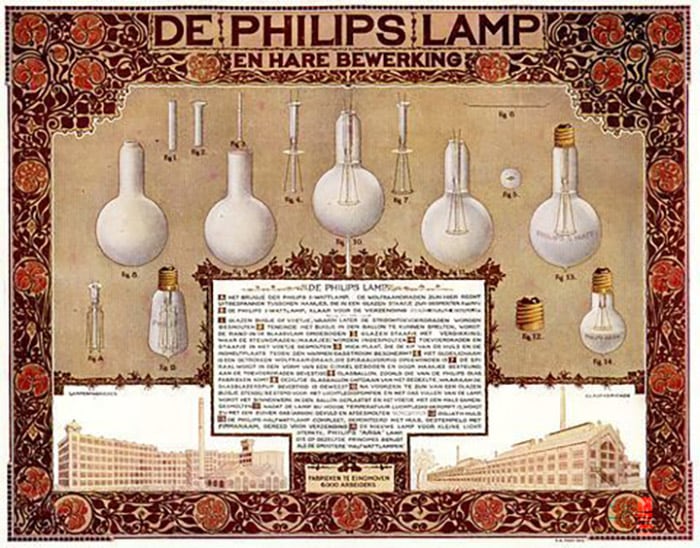

Developments over time are readily apparent in Philips' graphic advertising art. Consider the early years, between 1910 and 1924, for example. Prior to this, advertising was not very important for Philips. Product sales took place primarily in the business market at factories, offices and hotels. A lighting catalog was all that was required for customers to make their choice. The launch of the metal filament light bulb and the construction of electricity generation plants opened up the consumer market for incandescent lamps. An increasing number of households had access to electric lighting and this led to a real boost in advertising material. In 1909, Philips’ first advertising cards were designed by Eef Stoot, an accountant at the company who just happened to be good at drawing. These were followed by picture postcards and the company’s first advertising posters, which featured farmers and farmers’ wives in traditional costume. These posters were a success both in the Netherlands and internationally.

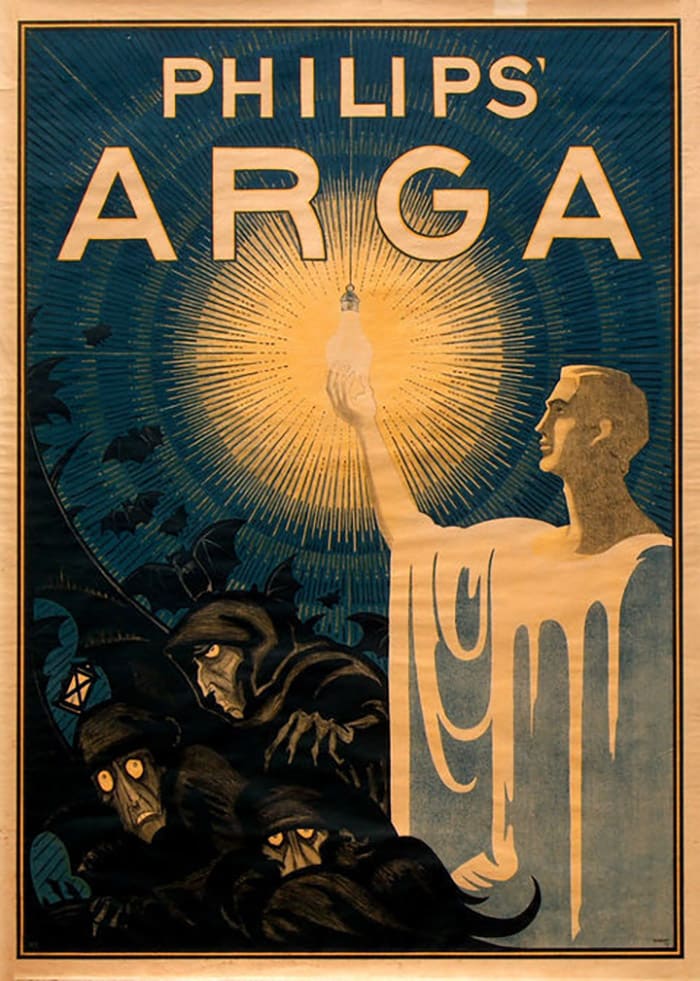

Sergio Derks, manager Philips Heritage Organization, explains: ‘From about 1916 Philips started collaborating with leading artists, including Leo Gestel, Theo Nieuwenhuis and Chris Lebeau. One year later an iconic poster was designed for Philips by Albert Hahn, a political cartoonist from a socialist background who was also a staunch antimilitarist. His illustration depicted a heroic figure using an incandescent light bulb to frighten away dark demons. This could be seen as a protest against the First World War, which was still in full swing.

Stars and wavelines

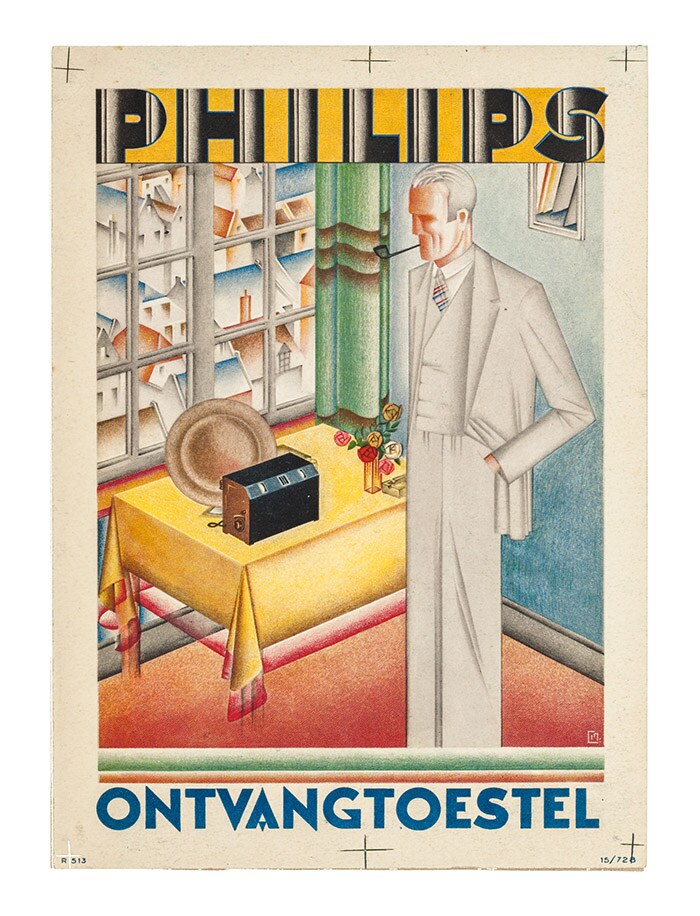

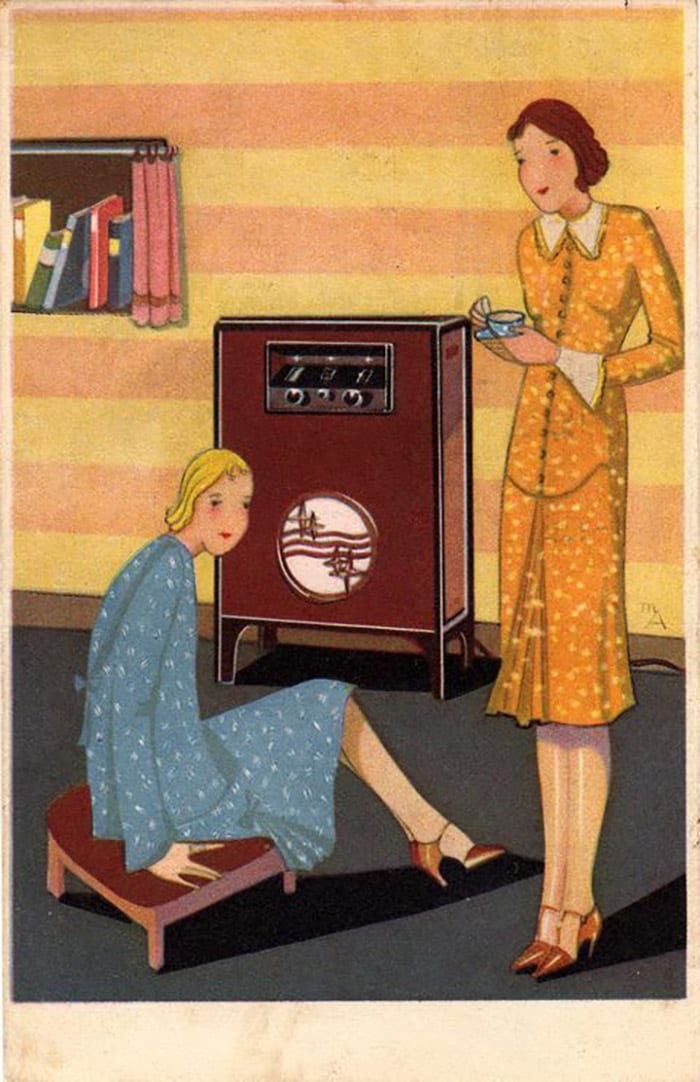

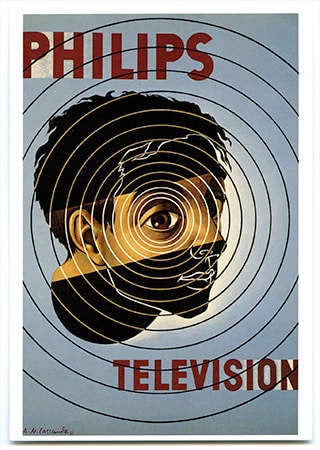

During the roaring twenties Philips enjoyed phenomenal growth, primarily due to the success of radio. The company became the largest manufacturer of radios in Europe and employed more than twenty thousand people. During this dynamic time, architect and graphic designer Louis Kalff was recruited to further professionalize the Artistic Propaganda department. Under his inspired leadership, from 1925 onwards, all Philips advertising material were given a clearer and more recognizable image. The influence of Japanese woodblock print art and Art Deco is evident in his designs and those of the other employees in his department. He standardized the Philips wordmark and laid the foundations for the Philips logo with the iconic stars and radio wavelines. ‘Before Kalff came to Philips, the company name was written in as many as twenty-five different ways,’ explains Sergio. ‘Each artist did it in his own way. What Kalff did was to create a clear and recognizable style and a standard lettering, and these were used for many years on both posters and products.’

Kalff's appointment proved to be a golden move. He brought talented artists and illustrators to Eindhoven. Not only from the Netherlands, but from all over Europe, such as Berlin-born Carl Probst and Russian Wladimir Bielkine, who fled during the Russian Revolution. They designed stylish, artistic advertisements that fit the prevailing zeitgeist. They designed stylish, artful advertisements that fit the prevailing zeitgeist.

Mathieu Clement was an up-and-coming talent that Kalff took under his wing. This paid off, because Clement very quickly started to flourish. His designs exuded a modern and affluent atmosphere, giving the products a high-quality and luxurious image. Sergio: ‘In addition to some amazing preliminary studies for a number of designs that were never completed, a charcoal portrait of Clement drawn by Kalff was also given to us on loan by the Clement family. A moving piece, particularly because Clement passed away shortly afterwards. He was only 23 years old and died of an infection of the adrenal gland.’

Let’s go to the movies

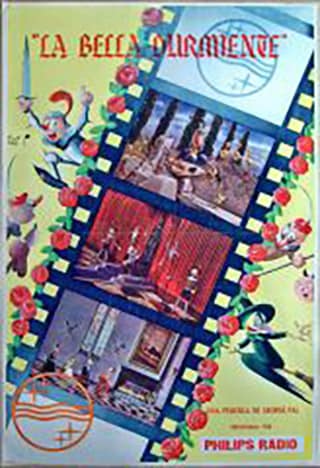

The year 1929 marked the start of difficult times. The crazy roaring twenties were brought to an abrupt end by the Wall Street crash. Philips was also affected by this and by 1934 the company had only a small department of advertising designers. When the Second World War broke out in September 1939, advertising was put on the back burner. At the same time, during the 1930s new forms of advertising were starting to emerge, like cinema advertising films.

Sergio: ‘The advertising films made by George Pal and later by Marten Toonder and Joop Geesink are legendary. Pal, a Hungarian, was also a pioneer in the field of special effects. He produced twelve animated films for Philips, but due to the threat of imminent war he fled to the United States in 1939. In Hollywood he received seven Oscar-nominations for his work. We created a mini cinema in the museum with the old cinema seats and original posters. Here you could watch a clip from Prins Electron, a puppet animation film made by Joop Geesink in the 1950s. The quality was still incredibly good.’

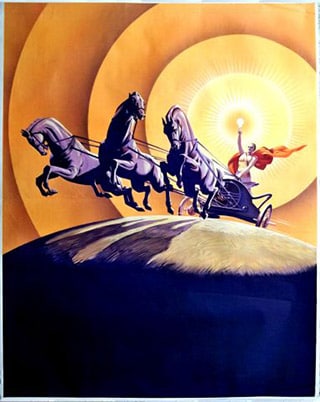

Hero riding a chariot

Better times dawned after the liberation. Society began to recover and sales of Philips products also picked up. This optimism can be seen in the graphic work from this postwar period. One impressive example is the poster ‘Return of the light’, which was produced immediately after the liberation. Just as in the poster from 1917, here too we see a hero bringing light into a dark world. On the chariot the circular Philips emblem with the stars and wavelines is just visible.

Sergio: ‘This is a very special artwork. The poster was placed immediately opposite the poster by Hahn. The subject was the same, but one poster was produced during the First World War, and the other immediately after the Second World War. If you turned round, you could see both posters and pick out the differences.’

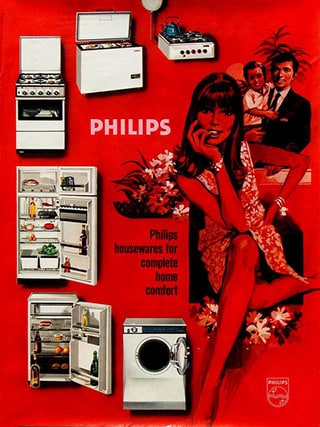

Farmer’s wife, pin-up or housewife

In the 1950s and ’60s there was a sharp rise in prosperity. People started to earn more and were able to afford electrical appliances that made life more enjoyable and made housekeeping easier. It wasn’t long before radios, TVs, gramophones, as well as refrigerators, washing machines and vacuum cleaners were flying off the shelves like hot cakes. ‘Domestic appliances had a particularly big impact on women’s daily lives,’ Sergio explains. ‘You could even say that these products contributed to emancipation, because women simply had more time for other things, such as work outside the home, study and relaxation.’ This change in the role of women also resonated in advertising. From the 1960s onwards, there was a greater focus on the modern, self-assured woman looking self consciously ‘into the camera’.

Faith in technology

Many of these illustrations were made by Willy Pot, who was also responsible for the series of posters that promoted the importance of technology. Four shop window displays, in which a young boy is seen playing with an Electronic Engineer kit, were shown in the exhibition. ‘In the 1960s people had endless faith in technology,’ Sergio explains. ‘Technology could be used to solve any given problem. At this time Philips needed to recruit a lot of engineers. The company produced electronics kits which, with the help of the corresponding advertising, were intended to encourage the younger generation to choose a career in science and technology. We regularly have visitors to the museum who tell us that it is thanks to these technology-based kits that they chose their current career path.’

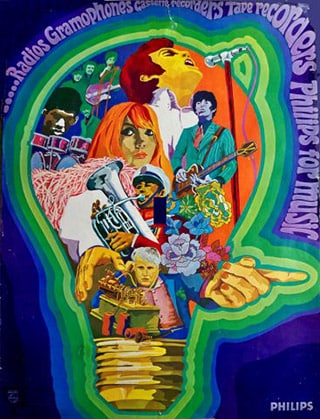

Youth in the sixties also developed an interest in other things. It was the era of pop music and the rise of youth culture. Philips advertisements responded to this and focused on this promising target group with trendy pop art images. Less and less use was made of graphic illustrations. Sergio: “From the 1960s, drawn and painted illustrations slowly disappeared into the background and made way for photography. Yet even today these works of art still have great power and beauty.

Exhibition Eyecatchers

Exhibition Eyecatchers was on display at the Philips Museum from March 25, 2022 through March 15, 2024. The exhibition included original posters from 1917, as well as a preliminary study: a poster painting that we were able to take on loan from the HSG in Amsterdam. It was a small miracle that both expressions were preserved in such a cool condition. Especially when you consider that posters were made for one-time use and then usually discarded. It is thanks to collectors and archives that we were able to display this magnificent collection in our museum.

The Eyecatchers exhibition made grateful use of the collections of Frans Wilbrink, the heirs of Mathieu Clement, ir. P.L. Vrijdag, IISG and the Philips corporate archives.

The book “Mathieu Clement, Artist by Nature,” by Ans van Berkum, Cathrien Clement and Peter Thoben is for sale in the Philips Museum museum store.