The April-May strikes of 1943 in Eindhoven

Courageous and life-threatening

For many Dutch people, the 1943 April strike is an unknown phenomenon. While this strike is the largest in all German-occupied territory. About 500,000 Dutch people participate and 175 fall victim to the German countermeasures. Those countermeasures are very strict; in case of gatherings of more than five people, or if there are protests or people call for a strike, there will be sniper shooting... Anyone who goes on strike and is arrested will be sentenced to death by the Standgericht. The reason for the strike is the ordinance on 29 April 1943 that all Dutch former soldiers, some 300,000 in total, are obliged to report to work in Germany. In protest, employees of machine factory Stork in Hengelo laid off work. Soon the strike spreads throughout the Netherlands.

Eindhoven and the German occupation

Eindhoven is an important city for the Germans. Philips is based there and the factory is a Rüstungswirtschaftliches Betrieb. In other words, a company important to the German war industry. Management in the Netherlands is under the authority of a Verwalter, a German who oversees the functioning of the company on behalf of the occupying forces. Directly below this, the factories are managed on a daily basis by five board members, including eng. Frits Philips.

Red, white, and blue flags

The strike is quickly picked up at Philips. On Thursday afternoon April 29, probably after a phone call from the Stork machine factory in Hengelo asking if they were also on strike there, it is decided to take the first action. Some Philips employees reportedly leave work that day. In the early morning of Friday 30 April, illegal pamphlets are distributed among the Philips staff with the appeal: "On Friday, everyone comes to the factories, but don't work that day. From Saturday onwards, everyone stays at home!!!" (At the time, Saturday was still a working day.) Despite the strict German surveillance of the factories, this appeal was heeded by almost the entire workforce. Most factory managers and chiefs showed restraint and made no attempts to put their staff to work. Moreover, the State Mines went on strike. They supply the gas for part of the Philips plants, needed in the production of light bulbs. With the supply of gas stagnating, they could not even continue working. To limit the damage and cool tempers Frits Philips decides, in consultation with the Verwalter and the Rüstungsinspektion (the body that takes care of army orders), to let people off the next day, Saturday 1 May. In itself, this is very unusual, as Frits Philips and the Rüstungsinspektion thus go against the orders of the Reich Commissioner Seyss-Inquart. May 1 is a day off during the German occupation, but this year Seyss-Inquart decides a day in advance to continue working as usual, because then the Germans can better control whether there is a strike and by whom.

The SD sidelined

In The Hague, police and SS chief Rauter is trying to keep things under control. How does he plan to do this? First, he appoints a Kommandeur of the Schutzpolizei in all regions, and in Brabant this will be Major Herbert Furck. Next, all SD offices, including those in Eindhoven, are put on-hold. That means they have to stop all work and await orders from Major Furck. But they don't come. Although Frits Philips has stipulated that Saturday remains a day off, Seyss-Inquart does not agree. He has the mayor called on Saturday to say that work has to be done anyway, but by then it is too late. Philips cannot get its workers into the factory that day, indeed, they are already out on the streets. According to eyewitnesses, open trucks drive through Eindhoven, decorated with Dutch flags, full of striking Philips workers singing songs, waving red-white-and-blue flags and calling for a strike... In the course of Saturday, the news travels down to Major Furck in Den Bosch. He is furious and decides to send the Schutzpolizei to Eindhoven the next day; order must be restored.

The first arrests

Now the first arrests are also taking place. Everyone is required to be inside at eight o'clock in the evening. Philips employee Feik Fast meets the German Schutzpolizei, the so-called 'green police', and writes in his diary: 'The next day I go for a walk with Rie, when it is almost eight o'clock; exactly at eight o'clock the raid van with green police arrives, so we have to hide for a while with strange people in the house, a few streets away from us. Then run through the gardens on their way home! Everyone, whom they can get hold of, they take away.' The Philips management places the following appeal in the Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden: 'To the personnel of N.V. Philips. The management of N.V. Philips deems it necessary to urgently point out to all personnel members that they should resume work on Monday 3 May on time. Anyone who does not do so will be exposed to the harshest measures, arising from the proclamation of martial law'. Frits Philips writes about this in his autobiography 45 Years with Philips: 'On Monday 3 May, the Germans appeared to have done the stupidest thing they could do that moment. People who wanted to go to work on Monday morning suddenly saw heavy German surveillance at the gates, upon which many did not even enter. Worse was that, due to an otherwise understandable precaution by the municipal gas company, our factories were without gas. The gas supply by the State Mines had stagnated for a short time due to several strikes, but had since resumed, whereupon the municipality had decided to fill up the gas holder for the population first, before supplying gas to Philips. At the plant, however, the reaction was: 'You see: no gas! So they are still on strike in South Limburg. Then we'll go home too". Our factories were already sparsely populated, and those who were there began to feel more and more uneasy. Finally, they too walked out of the gate.' The Schutzpolizei tries to track down strikers with the help of Dutch policemen. When they see a Philips employee walking down the street, they ask him, what he is doing there. He truthfully tells them that he has been sent by his boss to Philips workers to persuade them to go to work anyway. He is not believed and is sentenced to death a few hours later. Almost simultaneously, Frits Philips is imprisoned. His son Anton remembers his mother telling his father at the time: 'Frits, it's actually a good thing you were captured, because imagine if you had made it through the war and you had never been imprisoned!' When the German arresting him then asks: 'But Mrs Philips, do you think we are going to lose the war?' she replies: 'Do you doubt that?'

Standgericht in Headquarters

The SD in Eindhoven is ordered by The Hague to set up a Standgericht, i.e. a room in the Philips building, containing a judge (an SD employee with a legal background is already sufficient), a prosecutor and a lawyer. Often this function is performed by an SD employee, but in Eindhoven the Philips lawyer is asked, to defend the accused. In the end, he is not listened to at all. The Germans are only concerned with deaths, there cannot be too many nor too few. The only aim is to frighten and end the strike quickly.

Executions at the Philips site

To get hold of suspects, the Schutzpolizei orders Dutch policemen to choose people who can be arraigned from the growing stream of arrestees. Seven random men fall victim. The verdict is fixed in advance: the death penalty. Rauter receives the telex message with the verdict and sends back his ratification by return. When the willing workers leave the Philips factories at the end of the afternoon, they have to watch German soldiers in front of the bunker near the glass factory carrying out the sentence of: Jan Gerrit Eilers, married, father of one child, aged 32 Johannes Cornelis Wilhelmus Gielen, aged 36 Pieter Jan Hendrik Kempen, aged 19 Willem van Beek, married, father of a child, 36 years Petrus Jacobus Verhoeven, married, 32 years Gerardus van Werts, aged 34. In Eethen, a group of agricultural workers join a demonstration in front of the striking dairy. Some are arrested and that same evening one of them is shot in front of the Philips factory; Simon van Zandvliet, 27 years old Of almost all those executed during the April strike, we know where they lie and most have been found. Of the 55 executed, there are seven victims from Eindhoven of which nothing is known. As far as we know, even after the war there was no investigation among arrested Germans to find out where the remains might be.

Frits Philips as a pawn

In his autobiography Frits Philips writes: 'One of them was arrested while he was working in his little garden. Asked by the Germans whether he was on strike, he replied that he was on leave this week. They then wanted to know whether he would have been on strike, if he did not have a week off. In all honesty, he admitted that he would have joined the strike. He too had to come before the firing squad.' Frits Philips does not yet realise that his life is now hanging by a thread. Rauter is furious and threatens to have only directors executed from now on. This makes Frits Philips a pawn on a macabre chessboard. That same evening, the Germans also run loudspeaker vans in the surrounding villages where many Philip workers live. The message is crystal clear: if the population wants to prevent engineer Philips and three other directors from being shot, everyone must go back to work. That's enough, the strike is broken and people go back to work. That same evening the SS Scharführer Cremer reports via telex, proudly to The Hague; AT PHILIPS STRIKE BROKEN, 75 PER CENT WORK AGAIN. PHILIPS MANAGEMENT IMPRISONED. Frits Philips is detained in Haaren and from there transferred to Sint-Michielsgestel. After being held hostage for several months, he is released on 20 September 1943, a year before the liberation of Eindhoven.

Further investigation reveals that this must have been Jan Gerrit Eilers. A man from Amsterdam with his heart on his sleeve. He was busy in his garden on Eindhoven's Boerhaavelaan on his day off and just gave the wrong Eindhoven policeman an honest answer, he had to pay for it with his life.

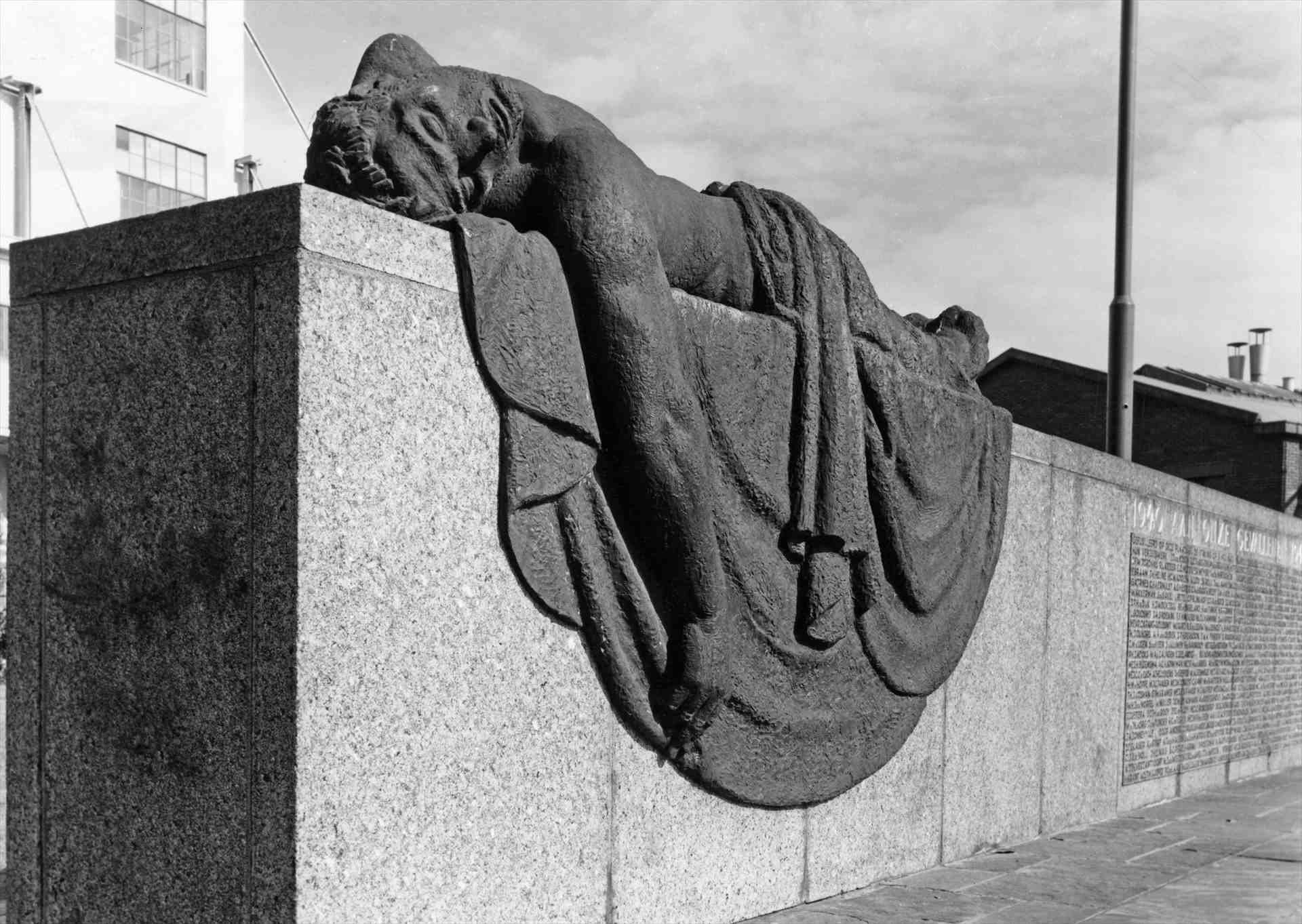

The 'Monument for the Fallen' can be seen on the former Philips terrain of Strijp-S in Eindhoven. Unveiled by Frits Philips in 1950, it is placed here in memory of Philips employees and others that were executed by the Germans because they stopped their work during the April-May strikes.

The content of this article is based on the following literature: Erik Dijkstra, Jan Morsinkhof, Jan-Cees ter Brugge, Staken op leven en dood, Amsterdam 2023 Frits Philips, 45 Jaar met Philips, Rotterdam 1976 I.J. Blanken, Geschiedenis van Philips Electronics N.V., deel IV: Onder Duits beheer, Zaltbommel 1997